HTTP status codes accompany every response from a web server, but most of the time they remain unnoticed until something goes wrong. At the same time, the status code is what defines the overall outcome of request processing, regardless of the response body.

For web testing, especially when working with APIs, correct interpretation of HTTP status codes is essential. They show how the server understood the request, whether the operation was performed, and what result was produced at the protocol level.

This article explores the role of HTTP status codes as part of HTTP semantics and analyzes common situations where the response status and the response body are inconsistent with each other.

HTTP Status as a Protocol-Level Signal

Every server response starts with a Status-Line: the protocol version (HTTP/1.1), a three-digit status code (200), and a short reason phrase (OK). The status code defines the general outcome of request processing – success, the need for additional actions, client errors, or server failures.

curl -I https://krasoff.com/

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx

...An HTTP status code does not represent business logic and does not depend on internal application implementation. It is a standardized way to communicate how request processing ended at the protocol level. Choosing the correct status code ensures predictable behavior not only in browsers, but also in automated systems such as API clients, test frameworks, proxies, and CI/CD pipelines.

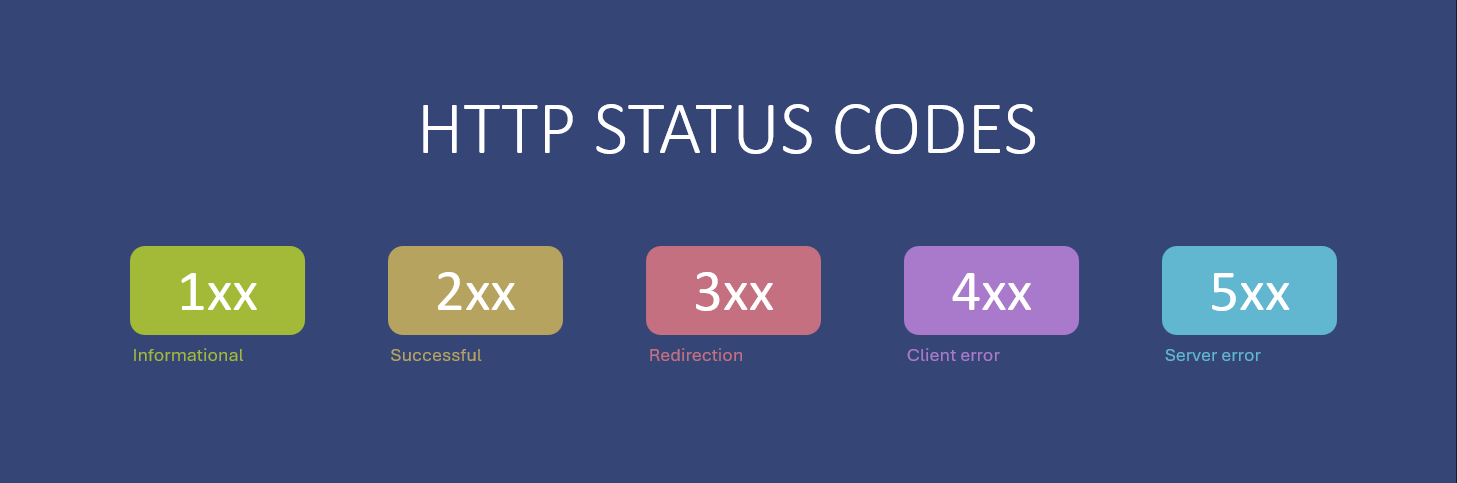

HTTP Status Code Classes and Their Semantics

HTTP status codes are divided into five classes, each representing a specific type of result:

1xx – Informational responses

Indicate that the request has been received and processing continues. These codes are rarely seen in everyday web interactions but are used in protocol-level scenarios, such as waiting for request body transmission (100 Continue) or protocol upgrades (101 Switching Protocols, 103 Early Hints).

2xx – Successful responses

Indicate that the request was successfully processed. Different codes clarify the nature of success: resource retrieval (200 OK), creation (201 Created), asynchronous acceptance (202 Accepted), or successful processing without a response body (204 No Content).

3xx – Redirection responses

Inform the client that an additional request to a different URI is required to complete the operation. Some codes change the HTTP method (303 See Other), while others preserve it (307 Temporary Redirect, 308 Permanent Redirect).

4xx – Client errors

The server understood the request but cannot process it due to a client-side issue: invalid syntax (400 Bad Request), missing authentication (401 Unauthorized), insufficient permissions (403 Forbidden), missing resources (404 Not Found), conflicts (409 Conflict), and similar cases.

5xx – Server errors

The request is valid, but the server failed to process it due to internal problems such as application failures (500 Internal Server Error), temporary unavailability (503 Service Unavailable), or gateway timeouts (504 Gateway Timeout).

These classes form the foundation of HTTP behavior, while individual codes within each class help describe the exact reason for the outcome.

Semantic Consistency Between Status Codes and Response Bodies

Although the response body may contain additional details, the HTTP status code defines how the response should be interpreted. When the status code and the response body contradict each other, the meaning of the response becomes ambiguous.

This situation is common, for example, when an API returns:

200 OKwith an error message like{"error":"not found"}500 Internal Server Errorfor invalid input data404 Not Foundfor an existing collection that simply contains no items, e.g.[]

In such cases, the status code loses its meaning, and the client must parse the response body to understand what actually happened. This breaks HTTP semantics, complicates testing, and makes API behavior unpredictable.

Correct examples include:

201 Createdwhen a resource is created, with a URI pointing to the new resource400 Bad Requestfor syntax or structure errors422 Unprocessable Entityfor semantic validation errors409 Conflictwhen the current resource state is violated401 Unauthorized Errorand403 Forbiddento distinguish between missing authentication and insufficient permissions

Structured error formats, such as RFC 7807, do not replace HTTP status codes – they only complement them with additional context.

Case Study: 302 Found, Redirects, and Client Behavior Mismatch

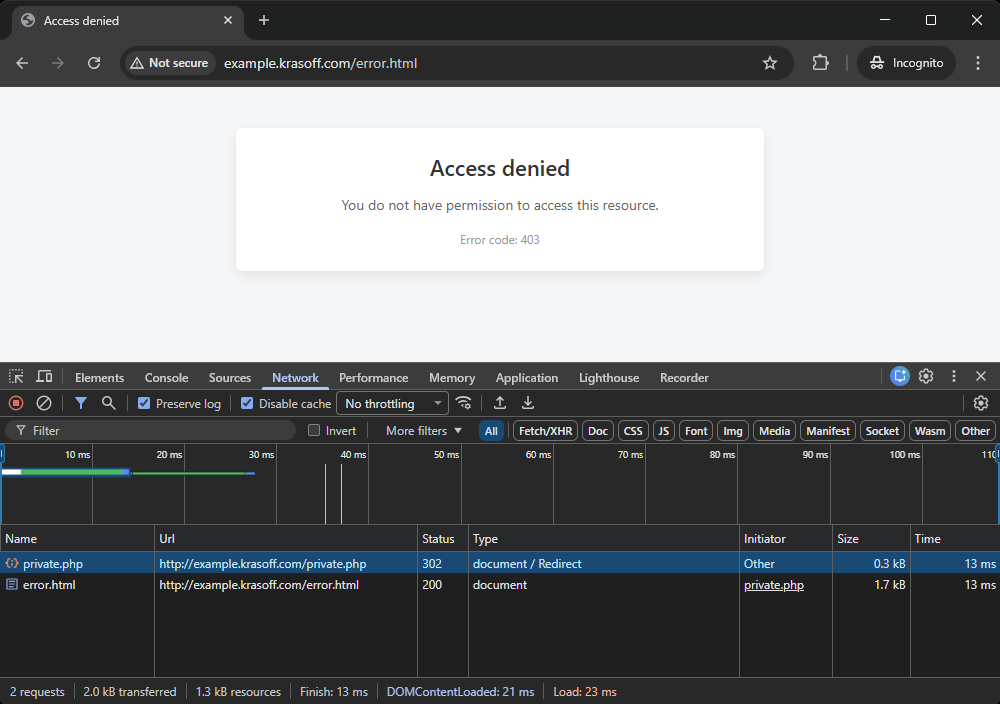

While analyzing the behavior of a web server, I encountered a situation that clearly demonstrated a mismatch between the HTTP status code and the actual response content.

When accessing a protected URL, the server returned 302 Found and redirected the client to an error page. In the browser, everything looked correct: the user was automatically redirected to /error.html and saw a neutral access-denied message.

However, inspection of the raw HTTP exchange showed that the original response contained not only the Location header but also a JSON response body with private data. When accessing the same endpoint using curl, the client received the full response:

curl -i http://example.krasoff.com/private.php

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Location: /error.html

{

"status": "redirect",

"message": "Authentication required",

"private": {

"user": {

"id": 42,

"full_name": "John Doe",

"email": "john.doe@example.krasoff.com",

"roles": [

"admin",

"finance"

]

},

"session": {

"session_id": "63bcd4d879bf4a09386ffd3c",

"expires_at": "2026-01-26T02:11:31Z"

},

"api_key": "6cc44889-0e2c-4d81-87d2-f5d41c3da472"

}

}The browser followed the redirect and hid the original response. Meanwhile, HTTP clients without automatic redirect handling – as well as proxies, loggers, and testing tools – received and processed the response body in full.

From a protocol perspective, this behavior is incorrect. The 302 Found status indicates that the client should repeat the request at a different URI and does not imply that a protected resource representation should be transmitted. In this case, the status code and response body contradict each other: access appears to be denied, yet the data is still being sent.

This example shows that browser behavior does not reflect the actual HTTP exchange. Inspecting status codes and response bodies at the protocol level makes it possible to detect issues that may remain invisible during manual browser-based testing but surface when working with APIs, automated clients, or intermediary infrastructure.

Common Scenarios Demonstrating Correct and Incorrect Status Code Usage

HTTP status codes are easiest to understand through common request scenarios.

Resource Creation

A successful creation returns 201 Created, typically with a Location header pointing to the new resource.

If creation fails due to a state conflict, such as a duplicate unique field, 409 Conflict is appropriate.

Data Retrieval

A successful request returns 200 OK.

If data has not changed since the last request, the server may return 304 Not Modified.

For existing collections with no elements, 204 No Content may be used to indicate the absence of a response body.

Updates

Successful updates may return 200 OK (with a body) or 204 No Content (without one).

State conflicts should return 409 Conflict.

Semantically invalid data should result in 422 Unprocessable Entity.

Deletion

Successful deletion usually returns 204 No Content.

Access Errors

Missing authentication results in 401 Unauthorized.

Authenticated users without sufficient permissions receive 403 Forbidden.

Resource Relocation and Access Flow

In some scenarios, the server does not return the requested resource directly but instructs the client to repeat the request at a different URI.

A permanent relocation should be communicated using 301 Moved Permanently, or 308 Permanent Redirect when the HTTP method must be preserved.

Temporary changes in resource location or access flow are represented by 302 Found or 307 Temporary Redirect, with 307 explicitly requiring the original HTTP method to be reused.

Format and Media Errors

Malformed JSON or missing required fields lead to 400 Bad Request.

Unsupported request formats result in 415 Unsupported Media Type.

Unacceptable response formats cause 406 Not Acceptable.

Load, Timeout, and Routing Errors

Rate limits are indicated by 429 Too Many Requests.

Temporary unavailability returns 503 Service Unavailable, often with Retry-After.

Routing failures may return 502 Bad Gateway or 504 Gateway Timeout.

Client Errors vs Server Errors: Responsibility Boundaries

Client-side errors (4xx) indicate that the request was understood but cannot be processed due to invalid input, missing permissions, or state conflicts.

Server-side errors (5xx) indicate that a valid request could not be processed due to internal failures. Unlike 4xx errors, they do not reflect request correctness and signal issues within the system itself.

The Role of HTTP Status Codes in Web Testing

HTTP status codes are formal indicators of request outcomes. They allow testers to verify:

- whether the response matches protocol semantics

- whether the status code aligns with the response body

- whether client and server errors are properly distinguished

- how the system behaves under load

- how edge cases such as conflicts, empty responses, delays, and outages are handled

When working with APIs, HTTP status codes become a primary diagnostic signal. They define operation boundaries, reflect server state, and reveal inconsistencies independently of internal implementation details.

Why HTTP status codes really matter

HTTP status codes form a structured language for communicating request outcomes. They reflect protocol semantics rather than business logic and define how server responses should be interpreted.

Correct use of HTTP status codes ensures transparency, predictability, and stability in web systems. For testing, they provide a reliable reference point for analyzing server behavior across scenarios, detecting inconsistencies, and assessing system health. When a response status accurately reflects the actual outcome and the response body complements that status, it creates a solid foundation for designing, maintaining, and testing APIs of any complexity.