If you've ever debated whether "login" means authentication or authorization, or heard colleagues use the terms interchangeably – you're not alone. In security-conscious systems, identification, authentication, and authorization form a tightly coupled, but distinctly separate-sequence of checks.

If you've ever debated whether "login" means authentication or authorization, or heard colleagues use the terms interchangeably – you're not alone. In security-conscious systems, identification, authentication, and authorization form a tightly coupled, but distinctly separate-sequence of checks.

As QA engineers, we have to understand what each step does, why it matters, and where things commonly go wrong is essential.

Let's walk through the trio, not as textbook definitions, but as real-world stages of a system.

Identification: "Who are you?"

Before a system can verify you, it first needs to know who it's verifying.

Identification is that very first declaration: "I am Alice" or "I am Bob". It's typically a username, email, phone number, device ID, or API client ID – any unique identifier that points to a specific record in the system. Example: Typing alice@example.com into a login form.

At this stage, the system isn't believing you yet. It's just figuring out which Alice to look up in the database.

The key requirement here is uniqueness. If two users can share the same identifier (e.g., duplicate emails), the whole chain breaks down. How can you authenticate or authorize someone if the system can't tell which user you mean?

Watch for cases where identifiers aren't validated for uniqueness, or where systems allow fuzzy matching (e.g., using specific Unicode in logins can be problematic due to compatibility, normalization, and potential login failures.). These can open the door to account confusion or bypasses.

A real-world example of this problem appeared in GitHub's password-reset flow in 2019. GitHub once lowercased user emails before comparing them, but then sent the reset link to the exact email provided by the requester. This created a subtle Unicode collision: the Turkish dotless ı lowercases to i, meaning mıke@example.org and mike@example.org would match during lookup – but the reset email could be sent to the attacker-controlled Unicode variant. GitHub patched the issue by ensuring that only the original, registered email address can receive password-reset messages.

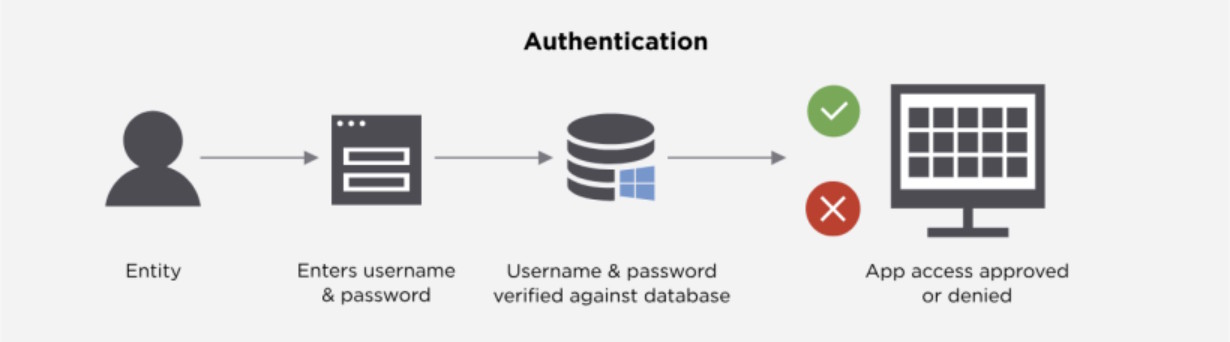

Authentication: "Prove it".

Now that the system knows who you claim to be, it asks: "How do I know it's really you?"

Authentication is the act of verifying that claim. It answers one question "Are you who you say you are?" This is usually done by checking something you know (password), something you have (phone with an authenticator app), or something you are (fingerprint).

Real-world systems most often use these approaches:

- Password-based (SFA): Fast to implement, fragile in practice. Still common, but rarely sufficient alone.

- Two-factor (2FA): Typically password + TOTP (Time-based One-Time Password, like Google Authenticator) or password + SMS code. Much more resilient to credential theft.

- Passwordless: Biometrics (Face ID, fingerprint), platform authenticators (Windows Hello), or FIDO2 security keys. Eliminates the weakest link-knowledge factors-entirely.

- API/service auth: API keys, signed requests (HMAC), or mutual TLS (mTLS). Here, the "user" is another system, so authentication means verifying the caller's identity, not a person's.

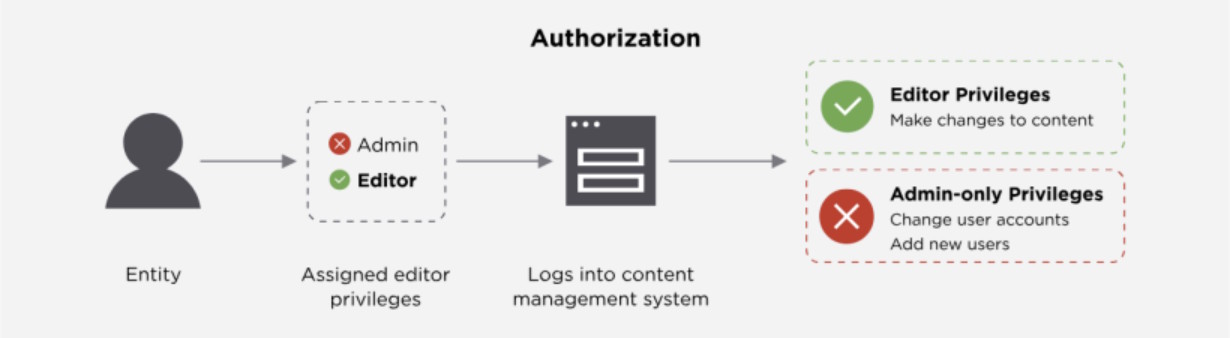

Authorization: "What are you allowed to do?"

Only after the system is confident in who you are does it decide what you can do. Authorization is where permissions come in: "Now that I trust you're Alice, what can Alice do here?"

This is where most critical security bugs hide. For example:

- A regular user accessing admin rights because the endpoint lacks role checks.

- An API may returning redundant information records, including some private data, even when the requester has no business seeing that field.

Common models you'll encounter:

- RBAC (Role-Based Access Control): "Alice is an Editor, so she can create and edit posts, but not delete them". Clean, scalable, and great for most apps.

- ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control): More dynamic. "Allow access only if department = finance, time < 18:00, and device.trusted = true". Powerful, but trickier to test exhaustively.

- OAuth 2.0: Often misunderstood as authentication, but it's fundamentally an authorization delegation protocol. When you "Sign in with Google," Google authenticates you, then issues an access token that lets the third-party app authorize actions on your behalf (e.g., "read your email contacts").

How the Three Work Together (and Why Order Matters)

Think of identification, authentication, and authorization as a pipeline:

- Identification sets the context: "This request is for Alice".

- Authentication validates the claim: "Yes, this really is Alice".

- Authorization applies policy: "Alice can edit her own drafts, but not publish or view payroll".

Skip step 2, and you've got unauthenticated authorization, an open door. (Yes, some public APIs do this, but intentionally and sparingly)

Final Thought: It's Not Just Semantics

Calling Authentication and Authorization the same thing isn't just a terminology slip, it's a design risk. Systems built without clear separation between "who you are" and "what you can do" tend to accumulate access control debt: hard-coded roles, scattered permission checks, and brittle security logic.

As QA engineers, we're uniquely positioned to catch these gaps, not by auditing code, but by thinking like an attacker with a valid account. After all, most breaches don't start with zero-day exploits. They start with legitimate access, misapplied.

So next time you're testing a login flow, or an API, or a "shared link" feature, ask yourself:

- Where does identification happen?

- How is identity proven?

- "Where" and "how" are permissions enforced?

The answers will tell you where to dig deeper.